At the Four Domes Pavilion in Wrocław, light turns into thought and concrete into emotion. This is the home of contemporary Polish art. But the first thing you notice as you arrive is the neighboring Centennial Hall.

The iconic Wrocław building immediately caught our attention with its monumental concrete dome, reportedly the largest in the world. In front of the hall, we discovered an elegant 106-meter-high mast. This work of art by Stanisław Hempel was part of the first post-war exhibition, the so-called Exhibition of Regained Territories, but today it serves more as a symbol of the connection between architecture, technology, and artistic perception.

The contrast between the massive hall and the subtle mast creates such a dynamic space that we almost missed our meeting. We had an interview with Iwona Dorota Bigos, manager of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Wrocław.

Where light touches concrete

“The Four Domes Pavilion in Wrocław is like a temple of light and silence. The monumental building by Hans Poelzig, built in 1912 in a mere eight months,” smiles Iwona Dorota Bigos. “Today, it would definitely take much longer.”

We sit in the café inside the huge glass-atrium that unites the museum’s wings into a single courtyard. She smiles, and I realise that although we’re inside a museum, the atmosphere is surprisingly alive. Light glides across the exposed concrete walls and the silence has a strange resonance—as though the architecture itself is breathing.

Mobile home for the homeless

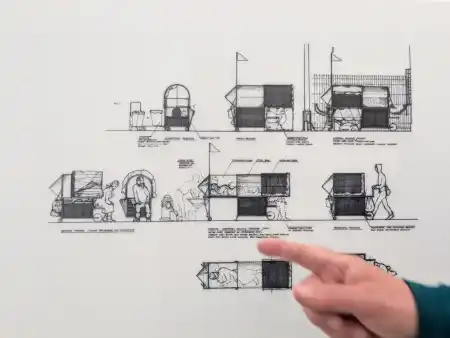

Right in the atrium, on the left, Iwona draws our attention to Krzysztof Wodiczko’s work, an experimental prototype of a home for the homeless. The meaning only becomes clear when we see photos of the first installation, directly under the Trump Centre in New York.

A collection that breathes its era

“Our pavilion is part of the National Museum in Wrocław,” explains Iwona. “But here we focus exclusively on contemporary art. We have a permanent exhibition of post-war Polish creation — a time when art survived totalitarianism, censorship and doubt.”

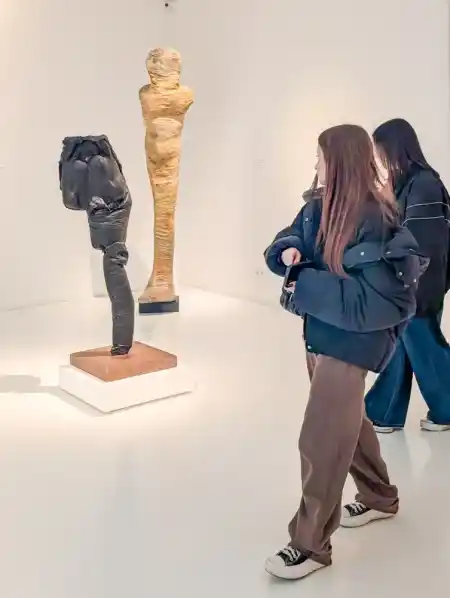

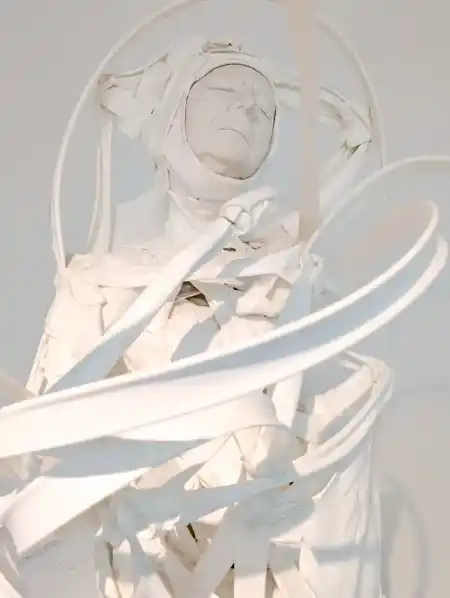

She stops at one of the monumental sculptures. “Magdalena Abakanowicz‘s works are about the human condition.”

“The Museum of Contemporary Art has 22,000 works in its collection,” she adds. “A large part of it consists of photographs, including some from the early 20th century.”

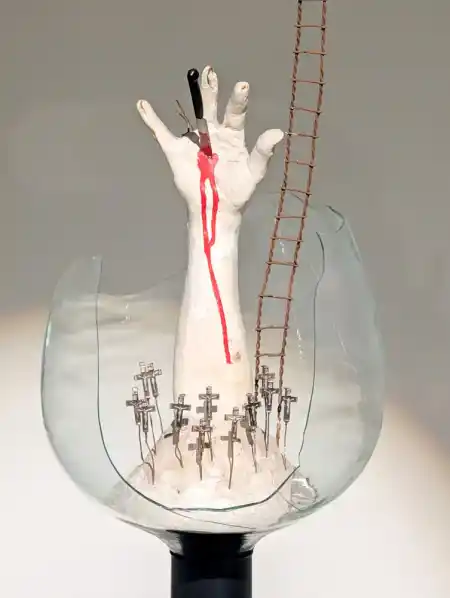

Art as provocation, not decoration

“”Every exhibition is a unique experiment,” continues Iwona Bigos. “Right now we’re showing a retrospective of Waldemar Cwenarski — Czułość. Powroty i poszukiwania (Tenderness: Returns & Explorations).”

“In addition to Cwenarski’s works, this exhibition also features pieces that inspired him and those that relate to his work in some way. One example is ”Bucza,” which is very relevant in its message.“

We also have a large, beautiful work by Marcin Maciejowski, in which we find inspiration from Picasso’s Guernica and Malevich’s Black Square. Or a work by Joanna Rajkowska, which refers to the current situation in Gaza.”

“People sometimes leave feeling moved,” Iwona says: “But art is not just for pleasure. Contemporary art should provoke.”

Wrocław as a laboratory of creativity

“Wrocław is a city of artists,” she goes on. “We have an Academy of Fine Arts, small galleries, experimental spaces. It’s an ecosystem where people know each other, discuss, react.”

“The Four Domes Pavilion is not just a museum. Every week, it hosts workshops, discussions, and film screenings. We want to be a lively meeting place for everyone,” explains Iwona.

Fantasy like oxygen

Our conversation turns to a subject that’s quiet but important. “People seem to be forgetting how to imagine,” I offer.

“Yes, yes,” she nods. “Without it we stop feeling. And without feeling—there’s no art.”

As I leave, the sun touches the domes and turns the walls gold.

Curatorial highlights you mustn’t miss

The permanent exhibition at the Four Domes Pavilion is like a journey through Polish modern and contemporary art. It begins with the inter-war pioneers—Chwistek, Witkiewicz, Strzemiński—who with their experiments and theories shaped the aesthetics of following generations. Right away you sense the energy with which they played with colour, form and space.

Then we move into post-war art: the first modern art exhibition in Poland, 1948, where young abstract and surrealist artists experimented with new currents and Western inspirations. You notice the contrasts—colourists who “built the picture with colour” and more radical creators rejecting every convention.

The museum also includes works that reflect the cruelty of war and the Holocaust—for example Cwenarski, Szapocznikow, Wróblewski. There is a strange atmosphere: art makes you stop, think and feel. Later comes abstraction, lyrical gestures, experiments with matter—from Lenica to Gierowski—each piece with its own personality.

Contemporary Polish Art

Some works surprise with their play on structure, like Stażewski’s reliefs, or Tadeusz Kantor’s ready-made objects.

Hasior’s assemblages from everyday objects entertained us—why toss old things away? We remembered a royal family portrait by Joan Miró in Barcelona.

Gradually the exhibition moves into conceptual art and contemporary times: Tarasewicz, Twardowski, Ziółkowski and others blend gestural painting with literary or surreal motifs—a lot to take in. Even better, the museum is full of young people.

The permanent show overwhelmed us with variety, colours, forms, reflection of the times—and above all with that colossal space. Walking the gallery is like a dialogue with past and present, and although you could speak about each piece for a long time, the real experience comes only when you get up from your hotel bed and visit the museum.

If you lose yourself amidst the light and space (which happens often here), let these points guide you:

- Magdalena Abakanowicz – monumental textile bodies that talk about human existence in another way.

- Bucza – a quiet testimony of war that hits you hard.

- Joanna Rajkowska’s Gaza – an installation you cannot just look at. You have to feel it.

- The architecture of Hans Poelzig – sit in the middle of the halls and observe how the light shifts during the day.

How to get to the Four Domes Pavilion

- The Four Domes Pavilion (Pawilon Czterech Kopul) is located near the Exhibition Grounds of Centennial Hall in Wrocław.

- From the city centre take tram numbers 1, 2, 4 or 10 to the stop Hala Stulecia / ZOO. Open: Tuesday–Sunday; tickets available online or at the box office.

- A combined ticket also works for the National Museum in Wrocław.

- Be sure to combine your visit to the gallery with a stroll through the Japanese gardens.

Bonus: The poetry of Japanese gardens

They are located in close proximity to Pavilion 4 Domes.

“When you leave the Four Domes Pavilion, a different world awaits you,” says Iwona Bigos. “It’s not just architecture or an exhibition—it’s a walk through time and tranquility.” Just a few steps away from the modernist concrete and light-filled halls lies a Japanese garden, designed at the same time as the Pavilion: “Here you can stop, take a breath, and watch the play of water and shadows,” she adds.